Addiction, Trauma, Attachment and Dissociation: A Treatment with Limbic Psychotherapy®

Author'(s):Bernard MAYER*

Institut Européen de Thérapies Somato-Psychiques (IETSP),Association Française Pierre Janet (AFPJ), Paris, France.

*Correspondence:

Bernard MAYER, Institut Européen de Thérapies SomatoPsychiques (IETSP), Association Française Pierre Janet (AFPJ),Paris, France, Mail: mayer@ietsp.fr and www.ietsp.com.

Received: 05 Dec 2023; Accepted: 12 Jan 2024; Published: 19 Jan 2024

Citation: Bernard MAYER. Addiction, Trauma, Attachment and Dissociation: A Treatment with Limbic Psychotherapy®. Addict Res.2024; 8(1): 1-8.

Abstract

Within the range of methods amalgamating restricted verbal and non-verbal tactics, integrative therapies imbued with the complex neurophysiological facets of the condition present the best prospects. At the junction of physical and psychological dimensions, these "bottom-up" methodologies possess a distinct ability to activate the patient's neurophysiological reserves, while guarding against any susceptibility to suggestion on the part of the therapist. Targeted manual interventions, previously employed in TICE® [12], reinforce the initial effects, which fundamentally derive from the patient's innate self-healing capacities. The blockages arising from double or triple binds, often including those of a higher order, maintain this deregulated state of functioning in order to survive, because this is how the patient's nervous system was able to respond at the time of his or her trauma, as Pierre Janet already stated in the 1890’s : this constitutes the very essence of Limbic Psychotherapy®, an approach refined over decades of clinical experience with patients. Limbic Psychotherapy® regulates the limbic system by intervening directly at the neurophysiological level, in particular on the balance between the ventral and dorsal vagal pathways of the autonomic nervous system, as described in S. Porges' model. As a result, Limbic Psychotherapy® is both a psychotherapy and a neurotherapy, and is particularly effective in cases of structural and, above all, functional dissociation [33]. A clinical framework ideally suited to treating dissociative states, chronic stress, persistent pain, digestive problems, addictions and trauma. Thanks to the application of double tuning and specialized somatic interventions, the regulation of sympathetic/parasympathetic responses often begins as early as the first session, offering immediate relief to the patient.

Keywords

A Key Historical Concept: Dissociation

After Europe's 18th-century infatuation with Mesmer, a revolution took place when J.M. Charcot, the great neurologist at La Salpetriere (Paris, France), reproduced these experiments himself and succeeded in demonstrating that the trances of his hysterical patients were due to "ideas": it was then that the Paris Academy of Sciences decided to take an interest in the link between hysteria and hypnosis. Pierre Janet quickly became interested in this field and volunteered to treat hysterics at the hospital in Le Havre (Normandy, France). He was the first to understand the relationship between hysterical crises and hypnosis [1]. According to him,hysterical and highly hypnotizable patients suffer from traumatic dissociation. This fundamental discovery was published under the title "Psychological Automatism" [2].

In this work, Janet elucidates for the first time that intense emotions, distressing events, have the capacity to fracture individuality into two components - one that appears outwardly normal (albeit melancholic), and another that escapes consciousness, housing the traumatic incident and all its psycho-sensory and motor attributes. This compartmentalized facet also retains the memory of the event. This memory is recorded by severing links with the individual's ego and standard memory, thus immersing oneself in the subconscious, a term coined by Janet. Pierre Janet's model, by amalgamation, has made it possible to explain many illnesses and behaviors previously unnoticed by clinicians [3]. These include catalepsy, somnambulism, hysteria, automatic inscription and oration, and the conduct of mediums and spiritualists. According to Janet, these manifestations can be explained by the infiltration of dissociated fragments of one's personality into the subject's consciousness [4].

In the 1970s, researchers revived their fascination with the mechanism of dissociation in the field of psychology. The pioneers of this resurgence, exemplified by Spiegel [5] and notably Hilgard [6], argued for an innovative conceptualization of dissociation, calling their theory neo-dissociation. According to this contemporary perspective, dissociation manifests itself as a state of altered consciousness that unfolds along a spectrum ranging from the ordinary to the pathological. Cases of altered consciousness, such as absorption or daydreaming, represent facets of the banal, everyday manifestation of dissociation, while the most severe cases can be classified as pathological, encompassing phenomena such as dissociative fugue or, of course, multiple personalities.

It was in the light of this groundbreaking work that the American Psychiatry Association's leading compendium of global psychopathology, the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual), chose in 1980 to include dissociative disorders, the most emblematic of which at the time was MPD (Multiple Personalities Disorder). Due to insufficient training of practitioners in this new condition, it was nomenclaturally transformed into DID (Dissociative Identity Disorder) in the 1994 iteration of DSM-IV. As a result, the DSM's nosology acknowledges Pierre Janet's contributions, though without explicitly citing them. It should be emphasized that, according to Janet, dissociation is intrinsically traumatic and does not exist in a "normal", non-pathological manifestation.

The Importance of Functional Dissociation

The inclusion of dissociative disorders in DSM-III, coupled with their modification in DSM-IV, has prompted many clinicians worldwide to embark on research into dissociation and related disorders. This impetus led Van der Hart, Steele and Nijenhuis to write a comprehensive guide in 2006, entitled "The Haunted Self", which presents an alternative perspective on dissociation, rooted in Pierre Janet's early contributions: structural dissociation of the personality, or SDP [7]. In this framework, later validated by functional brain imaging studies, a traumatic upheaval precipitates the fragmentation of the personality into two or more components detached from the self. Initial dissociation generates an apparently normal part of the personality (ANP) and an emotional part of the personality (EP), while secondary dissociation results in one ANP and several EPs. Tertiary dissociation, on the other hand, gives rise to several ANPs and EPs. Each emotional part (EP) has an individual sense of self, remains outside the subject's usual awareness and suffers amnesia concerning the other dissociated segments. According to the authors, the definition of dissociative disorder encompasses not only DID, but also PTSD and other disorders of traumatic origin.

The severity of dissociative disorders such as DID or D-PTSD (a dissociative form of PTSD incorporated into the DSM-V in 2013) presents many complexities in the areas of identification and diagnosis [8,9]. In truth, given the amnestic nature of dissociated segments, patients often remain unaware of their own afflictions, frequently attributing their symptoms to more widespread disorders. Pathologies such as depression, suicide attempts, phobias, insomnia, persistent pain or eating disorders are the main reasons why people with dissociative problems consult us. Notably, the transition between ANP and EP or between several EPs proves extremely difficult to discern in clinical contexts [10]. According to some researchers, patients primarily seek professional help because of distressing intrusions that have a significant impact on their general well-being [8]. Nevertheless, these studies suggest that these distressing intrusions are dozens of times more frequent than switches between dissociated personality parts.

Under these conditions, the incidence of DID or D-PTSD in the urban population is only 1.5%, as reported by Martinez-Taboas et al. [11]. Nonetheless, municipal structures frequently receive visits from individuals with symptoms that appear to be akin to structural dissociation. Among the manifestations frequently evoked during consultations, patients often express experiences of internal division, a sense of being torn between different facets of their identity, and the perception of an inner voice - either solicited (as an advisory figure) or, more commonly, unwelcome (in the form of negative or threatening intrusions). The fact that patients are fully aware of their internal divisions is an essential indicator in these common scenarios. They themselves are the first to know about the various aspects of their personality and the contradictory demands placed on them on a daily basis. At present, these people are confronted with inadequate diagnoses and often undergo various therapeutic interventions - whether psychological or pharmacological - for long periods without achieving favorable results. This is why we believe it is necessary to correlate these numerous clinical cases with a new diagnostic category: Functional Dissociation®.

B. Mayer [12]: it resolves this paradox, as most patients in private practice suffer not from DID, i.e. structural dissociation, but from Functional Dissociation®, i.e. a type of dissociation that links the Structural Dissociation (SDP) of O. van der Hart and his colleagues with the Psychastenia of Pierre Janet, himself the founder of the concept of dissociation of the personality. Long anticipated by Bateson and his concept of double bind [13], Functional Dissociation® appears to be a more widespread disorder in the general population than DID. Janet's psychasthenia shares many attributes with Functional Dissociation®, as evidenced by the presence of obsessions, uncertainties and persistent contemplation. However, what distinguishes Functional Dissociation® from structural dissociation is that the detached components of the personality retain an interdependent awareness of their existence and engage in overt conflict. Furthermore, Functional Dissociation® stands in contrast to Janet's psychasthenia, which, according to the author, is virtually untreatable, due to its notable responsiveness to brief, effective therapeutic interventions. This significant contrast can be attributed to the contemporary arsenal of techniques and knowledge that surpass what was available to the eminent psychologist in his day. The diagnosis of Functional Dissociation® corresponds to a therapeutic approach[14] that directly targets the autonomic nervous system: Limbic Psychotherapy®. The following sections address the main theoretical and clinical foundations of Limbic Psychotherapy®.

Limbic Psychotherapy® and its neurophysiological basis

Frequently observed by our patients, the fracture of ego, consciousness or personality is the predominant symptom [15]. The individual struggles painfully with these inner divisions, wrestling with conflicting inclinations that prove insurmountable without external help. Their day-to-day existence is profoundly affected, often leaving them unable to act decisively. Months, even years, can pass in a state of perpetual indecision, uncertainty or persistent contemplation. It should be noted that, because of the symptomatic similarities between structural and Functional Dissociation®, the differentiations formulated by Van der Hart and his collaborators retain their relevance. Thus, these disorders can be categorized as psychoform and somatoform, positive and negative [16]. Naturally, this functional disintegration of personality is often associated with depression and other common illnesses (such as insomnia, phobias, anxiety, etc.). Cognitive and behavioral irregularities frequently coexist with functional dissociation.

Limbic Psychotherapy® is an integrative mind-body approach that directly addresses this dysregulation of the patient's neurophysiological system. Non-verbal and non-cognitive, it preserves the patient's freedom by not using suggestions, even metaphorical ones. The Limbic Psychotherapy® treatment is bottom-up: it acts without intermediary on the patient's limbic system, regulating the functioning of the amygdala and gabaergic systems. Cognitive change is a secondary effect of the treatment. From this point of view, addictions, compulsions and behavioral disorders are among the symptoms best treated by Limbic Psychotherapy®, due to their neurophysiological basis. Indeed, numerous studies have demonstrated the central role of the limbic system in pathologies associated with addictions and compulsions.

The Central Role Of The Limbic System

The central role of the limbic system is illustrated, for example, by Kalivas and colleagues [17], who have shown that the neurobiology of the patient and the subcortical areas of the brain play a decisive role in the activation of addictive behaviors. The amygdala in particular is involved in most stress and anxiety behaviours, which explains why this central nucleus participates in the neural network determining negative emotions, as Cardinal & colleagues [18] had already established, insisting on the close links that then draw the frontal cortex into a veritable vicious circle. By projecting its connections to several other central nuclei, the amygdala maintains the gabaergic circuit that is one of the main neuromediators of motivation. The glutamatergic system, meanwhile, links the above connections to the frontal cortex, among others. This is one of the reasons why deregulation of the limbic system affects the whole neurobiology of the brain, ultimately impacting on emotions, cognition and behavior: Limbic Psychotherapy® enables us to move from deregulation to regulation without calling on the patient's willpower [19].

The search for therapies best suited to addiction disorders is obviously nothing new. However, for several decades now, the approaches advocated have fallen into two categories: drug treatments on the one hand, and psychosocial treatments on the other [20]. According to recent research, the most effective drug treatments target the gabaergic system, and in particular the limbic nuclei of the subcortical brain [21]: a neuromediator antiepileptic such as gabapentin, in particular, is said to have significant effects on reducing cannabis-related symptoms. We shall see that Limbic Psychotherapy® acts at precisely this same level, by targeting the brain's limbic nuclei without intermediary. In addition, these researchers highlight the often beneficial, albeit moderate, effect of psychosocial interventions for patients suffering from addiction: approaches focusing on cognitive, behavioral or motivational factors are put forward, while emphasizing that they only derive their benefits in association with pharmacological treatment. As the authors point out, meditation is also an interesting alternative technique. Based on a synthesis of this clinical research, we can say that Limbic Psychotherapy® is one of the most suitable approaches for treating addictions, as it combines the advantages of the two types of intervention mentioned above.

From this point of view, it is interesting to note that, on all continents, addiction to certain substances or compulsive behaviors that can go as far as violence, are factors that directly affect self- control, social behavior and, in particular, private and professional life [22]. That's why it's important to diagnose and treat addictive behaviours as early as possible, as Koob and colleagues have already stressed [23]. This is all the more important as these same researchers had shown that prescribing powerful antidepressants such as fluoxetine, sertraline, imipramine or mirtazapine was not significantly effective in reducing substance use in patients.

How can Limbic Psychotherapy® significantly reduce addiction, including food addiction, or its symmetrical behavior, anorexia? Based on cutting-edge work in the field of pharmacotherapeutic interventions [24], it is possible to suggest that treatment with Limbic Psychotherapy® has a direct effect on the gabaergic system. Of course, this type of intervention also has an impact on other brain networks, since it acts at the level of the central nuclei, which are richly interconnected with the whole encephalon. However, GABA and its receptors are priority targets for Limbic Psychotherapy® intervention, as this neuromediator is the main inhibitory factor in the central nervous system. This characteristic also explains the remarkable efficacy of Limbic Psychotherapy® with regard to some of our patients' most frequent disorders: trauma and dysfunctional attachment.

Prevalence of Trauma and Attachment Disorders

Substance abuse, whether tobacco or alcohol, as well as compulsive behaviours such as bulimia or its opposite, anorexia, lead to dependence when a permanent disorder sets in. Addiction then manifests itself mainly as compulsive seeking of the substance concerned, loss of control at the time of consumption and a pronounced state of craving when the substance is no longer available [25]. Several authors have already demonstrated the close link between addiction and various bio-psychological factors, such as acute or chronic trauma, attachment disorders linked to a disturbed childhood, or a state of chronic stress. In their recent work, McCaul and colleagues [26] show, in particular, that anxiety, stress sensitivity and an enduring state of stress are the main factors contributing to the onset and then maintenance of dependence on certain substances or compulsive behaviors. By acting at the heart of the limbic system, Limbic Psychotherapy® is one of the most effective approaches for reducing trauma, dissociative states or chronic stress.

While the link between addiction and neurobiology has long been known, recent work finally clearly demonstrates the extremely close links between maladaptive behaviors, of which addictions are a part, and certain neurofunctional domains [27] such as executive functions, negative emotional sensitivity or incentive salience. In Kwako and colleagues' study of 454 patients, attachment disorders play a prominent role both in addiction and in deregulations of personality, cognition and other types of social behavior. This work highlights the link between the patient's neurobiology and the functional aspects of his or her experience: this is why Functional Dissociation® is one of the disorders best suited to treatment with Limbic Psychotherapy®. In fact, insecure attachment styles [28] are among the most frequently encountered in consultation.

With attachment disorders often manifesting themselves in childhood, it may seem logical that even children or young adolescents (up to the age of 17) can be affected by early-onset addiction. Looking specifically at alcohol, while "binge drinking" behavior is attested on every continent, the recent WHO report [29] considerably extends the prevalence of the disorder: among 68 low- and middle- income countries, children or adolescents regularly consuming alcohol represent from 1% to more than 50% of their age group. For these vulnerable and developing patients, integrative mind-body therapies offer the greatest potential, as they allow direct access to neurobiology without intermediaries such as hypnotic suggestion or, of course, psychotropic drugs. Thus, according to the latest research by Skylstad and colleagues [30], susceptibility to addictions in young patients is directly linked to depression and suicidality, chronic stress, neglect and, of course, post-traumatic shock. For these authors, campaigns to prevent and regulate access to alcohol should also be accompanied by brief therapy-type treatments, and above all by innovative approaches, as current solutions are both few and not very effective. In this respect, Limbic Psychotherapy® appears to be one of the most promising approaches for helping young people suffering from various addictions.

Limbic Psychotherapy®: essential principles

Recent psychiatric research has further underlined the relevance of a mind-body curative approach, showing that negative cognitive states (self-esteem, self-confidence and trust in others, pessimism vs. optimism, etc.) are directly linked to the patient's neurobiology: from this point of view, behavior and neurobiology are inseparable, and it is precisely this observation that Limbic Psychotherapy® exploits. Votaw et al. for example, studying a cohort of patients suffering from alcohol addiction, were able to validate a three- dimensional model basing addiction on negative emotional sensitivity [31], proposing a curative approach directly targeting the patient's affective states.

Regulation of the ventral vagal system

Limbic Psychotherapy® is based on the theory of structural dissociation of the personality, developed by Onno van der Hart and his colleagues after the work of P. Janet. This therapeutic approach focuses on the reunion of a personality fragmented into an Apparently Normal Part (ANP) and one or more Emotional Parts (EP) as a result of traumatic life experiences, whether acute or chronic, ancient or recent. As P. Janet pointed out earlier, the remedy for trauma requires intervention at the bodily level rather than in the realm of the mind alone. In 1927, he explained that "all the psychological facets are connected with the conduct of the whole individual". This elucidation explains why Limbic Psychotherapy® operates without intermediaries, directly addressing the origins of traumas rooted in the body and nervous system. This pioneering approach provides immediate access to the sources of suffering, dissociated from the traumatic personality.

Within this conceptual framework, the work of Porges provides interesting therapeutic tools. Neuroscientist Stephen Porges is the author of the polyvagal theory of emotion [32], according to which our autonomic nervous system is composed of two regulatory pathways: the dorsal vagal pathway maintains the stress and hypervigilance of post-traumatic states, while the ventral vagal pathway contributes to safety and social relationships. These two pathways thus echo Sherrington's antagonistic pathways. By acting on these neurovegetative pathways, Limbic Psychotherapy® relies on non-verbal modalities, offering access to traumatic experiences that cannot be expressed through speech [33].

Limbic Psychotherapy® opens up direct access to the dorsal and ventral vagal pathways: by releasing the resources hindered by the trauma, it activates the ventral vagal pathway, thus promoting healing. This is why the practice of mindfulness is an asset for the therapist, who accompanies the patient through his or her body and neurophysiology, step by step. During this therapeutic period, specific somatic interventions are mobilized. This type of approach is known as bottom-up, because it is rooted in the patient's neurophysiology: by providing direct access to the subcortical areas of the brain where emotions and traumatic memories are stored, the mind-body integrative approach is the most suitable tool for in-depth treatment of Functional Dissociation®.

Thanks to its immediate entry into the dorsal and ventral vagal pathways, as well as the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, Limbic Psychotherapy® is immediately effective. Porges' polyvagal theory elucidated that hyperactivity of the dorsal vagal pathway triggers traumatic states, dissociative states and developmental irregularities. This hyperactivity leads to a deficiency of the ventral vagal pathway and disrupts social bonds. Limbic Psychotherapy® establishes a connection with the primordial, instinctive pathways embedded in the nervous system over millions of years of mammalian evolution. By releasing the resources limited by trauma, this approach stimulates the ventral vagal pathway, promotes recovery and self-healing, and re-ignites the extinguished frontal lobes. Remarkably, positive results are often evident from the very first session, or within an exceptionally short space of time, inducing an immediate sense of relief in patients.

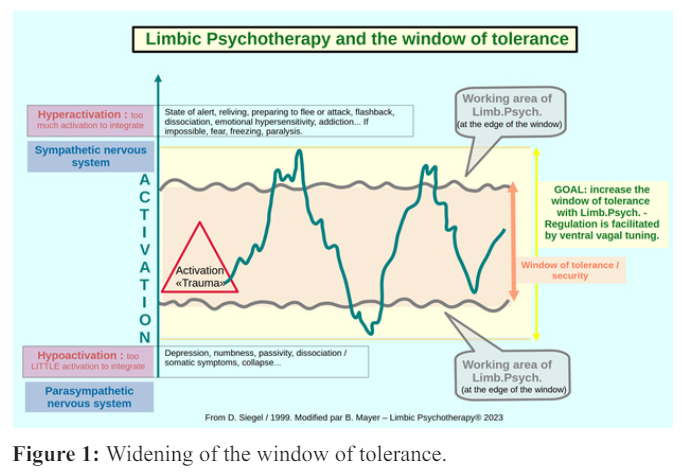

Widening the window of tolerance

The various stimuli and therapeutic body movements that form an integral part of the TICE® approach facilitate rapid identification of the emotional parts (EP) that are disturbing the patient. A dialogue is then established between these dissociated facets, leading to the integration of the whole personality [34]. The climax of the intervention is reached, when the window of tolerance takes on crucial importance. Precise regulation of sympathetic and parasympathetic pathway activation becomes imperative to restore balance between dorsal and ventral vagal states. This complex process requires a two-faceted attunement, encompassing both neurophysiological and relational dimensions (Figure 1). Such attunement enables the therapist to align himself as precisely as possible with the patient's neurobiology: this attunement then creates a therapeutic patient-practitioner dyad perfectly simultaneous with the therapeutic work, during which the patient always remains in full awareness. At this point, it's the patient's brain that does the work, supported by the therapeutic dyad, without any pre-established protocol, as we're simply following physiology. In this phase of the treatment, the patient is activated both in the present and in his past traumas, which resurface successively in the order in which they were encoded in the past.

It should be noted that this approach also optimizes efforts at the limits of the window of tolerance, underlining the importance of maintaining vigilance over the patient's reactivity, particularly in cases of heightened intensity, in order to avoid crossing these limits.

Within this therapeutic timeframe, new dialogues are initiated and consciously encountered, facilitated by targeted somatic interventions. The therapist remains vigilant to the individual's physiological state throughout the therapeutic process, carefully considering high and low activation states within their window of tolerance. Continuous monitoring of this state is essential to enable the use of regulation techniques in the event of excessive activation. In this context, the integration of mindfulness becomes an invaluable tool for the practitioner, who guides the patient through his or her bodily and neurophysiological experiences in a progressive manner throughout the course of therapy: the patient is no longer alone, and sometimes since many years... This methodology promotes non-verbal communication between distinct brain regions, varied emotional systems and, of course, the apparently normal part (ANP) and the emotional parts (Eps) [35]. The result is the initiation of the reunification process of the dissociated personality.

Addiction, compulsions or anorexia are often based on a faulty relationship with the past: during practical sessions, the patient is invited to feel the parts of his or her body that are linked to his or her physical or psychological suffering, in a benevolent and protective alliance. Focusing on the here and now mobilizes the autonomic nervous system and creates an opening for overcoming the traumatic past. From this point of view, S. Porges' polyvagal theory can be an effective ally: by activating the ventral vagal pathway to the detriment of the dorsal vagal pathway, the patient's social behavior can overcome both attachment and developmental disorders. Emma's clinical case, presented below, illustrates the relevance of these therapeutic principles.

Emma's clinical case

Emma, 20 years old at the time, was in her third year of business school and lived at home with her parents and younger sister. Her parents were present and loving, but Emma weighed 26 kg for 1m64: her anorexia was serious. Multi-hospitalized, medically monitored by several specialists including her GP, a nutritionist and a psychiatrist, she came to my practice to regain her weight, around 20 kilos. During the first appointment, the practitioner addresses the patient's various dissociated parts, her EPs, which manifest themselves through her ANP (apparently normal part). The patient describes how she fell into anorexia after being raped by a former classmate at the age of 15. Since then, her relationship with food has been totally dysfunctional: - "I don't eat fat anymore because I have a block... I'm afraid of sitting down and becoming enormous...". In an attempt to overcome this, she has undergone numerous treatments and hospitalizations, all to no avail.

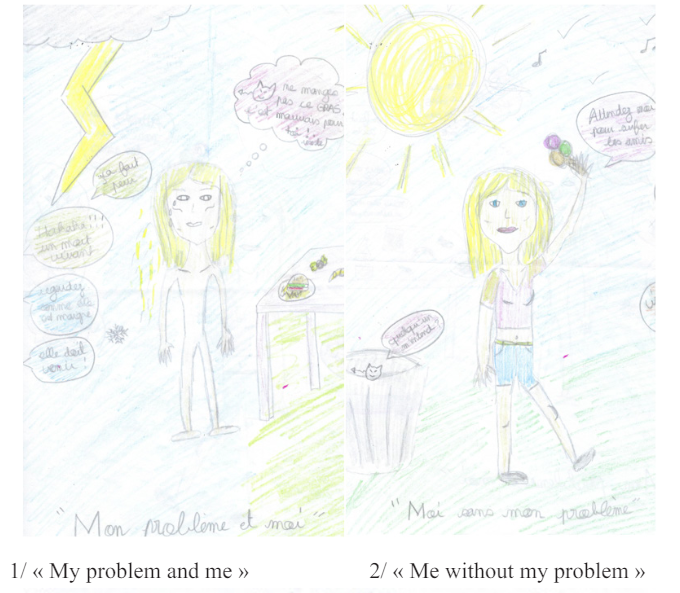

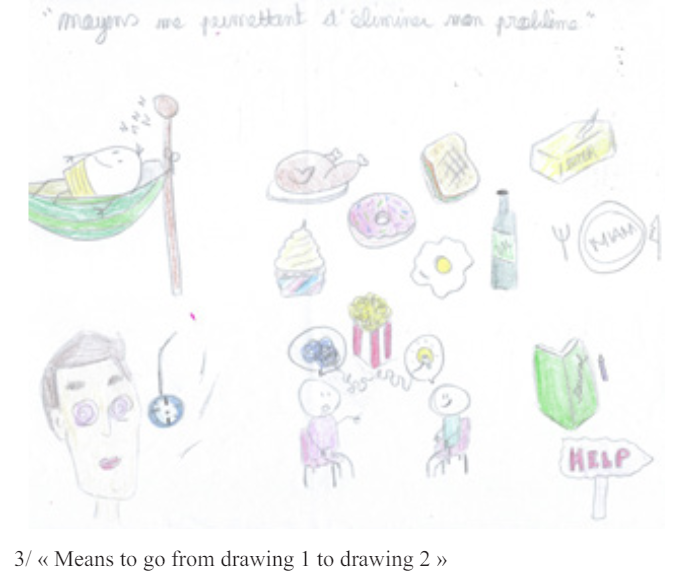

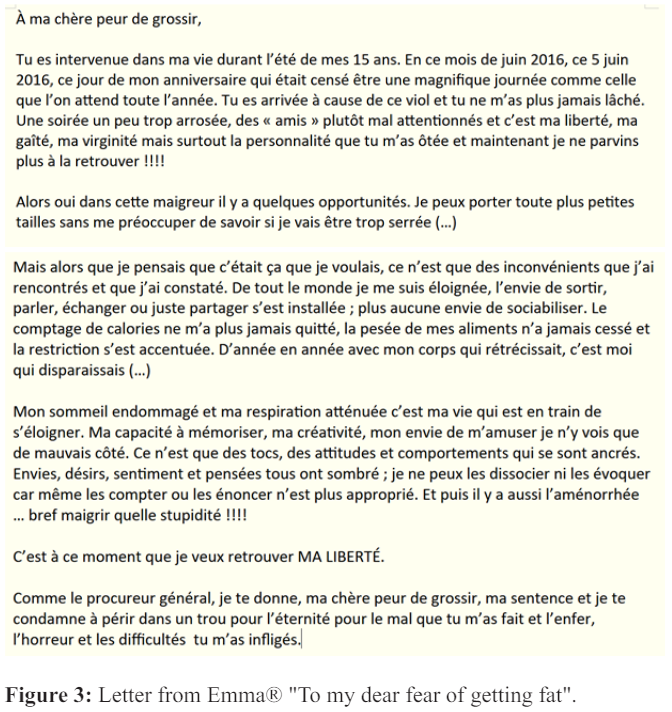

It soon becomes apparent that the patient also suffers from chronic stress and permanent anxiety: she feels perpetually insecure and desperately wants to control everything. In Limbic Psychotherapy®, the practitioner can use this discourse: - "I understand that there's a part of you that needs to control everything, because it wasn't possible before. You're very brave to have lived with this for so many years, and to have undergone so many treatments. Our work will go from the body to the brain and from the brain to the body. It's a question of working from the inside out, so as not to dissociate the body from the mind or the mind from the body. To achieve this, our intervention will not take place at the level of the frontal, logical, Cartesian, conscious, voluntary brain... because if this approach were effective, you would have done it long ago!" This time, the treatment takes place at the level of the subcortical, instinctual, limbic brain: this is where the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (among others) are activated independently of the will, in a word, it's the body speaking. To the patient: - "The work will consist in moving from the deregulation you're in to regulation, because since you were 15 you've been balanced in your deregulation". A paradoxical injunction concludes this preparation: "During this work, you are forbidden to relax and loosen up, because it is only the consequence of this therapeutic work that will bring you the expected physical and psychic appeasement". At the end of this first appointment, three drawings (Figure 2) and a Dissociative Letter (Figure 3) will be prescribed, which the patient will send to the practitioner before the second appointment. The Dissociative Letter is written either "To my dear anguish" or "To my dear fear of getting fat", but it could also be "To my dear need to control". Shortly afterwards, the three drawings received are as follows.

Figure 2: Three Emma® drawings.

The letter chosen was “To my dear fear of getting fat” Here are extracts (Figure 3).

Here is the translation of the letter:

“To my dear fear of getting fat,

You intervened in my life during the summer of my 15th birthday. In this month of June 2016, this June 5, 2016, this day of my birthday which was supposed to be a magnificent day like the one we wait for all year long. You arrived because of that rape and you never let me go again. An evening a little too drunk, some rather ill-attentioned "friends" and it was my freedom, my joy, my virginity but above all my personality that you took away from me and now I'll never be able to get it back !!!!

So yes, in this skinniness there are some opportunities. I can wear any smaller size without worrying about being too tight (…)

But just when I thought this was what I wanted, all I found were drawbacks. I distanced myself from everyone, the desire to go out, talk, exchange or just share took hold; there was no longer any desire to socialize.

The calorie-counting never left me, the weighing of my food never stopped and the restriction became more pronounced. Year after year, as my body shrank, I was the one who disappeared (...)”

At the second appointment, and of course with the patient's agreement, the Limbic Psychotherapy® therapeutic model consists of exploiting two sensory channels, sight and body: therapeutic touch is work without loss of consciousness and without influence or suggestions of the direct hypnotic or metaphorical kind. This type of intervention protects the patient from the practitioner's interpretations or worldviews. This approach is as effective as it is ethical: it opens the door to an ancient, pre-verbal type of learning, similar to that of cycling or swimming. The patient approves of this approach: "Yes, I want to get out of this without asking myself any questions".

At this point, the patient rates herself at 9 out of 10 on the SUD scale of 1 to 10 measuring her anxiety and fear of gaining weight, which corresponds to a very high level of activation with body tension, rapid heartbeat, tight throat and a feeling of oppression in the head. An intervention then consists of painful stimulation or percussion-vibration on a few points of the body, while at the same time instructing Emma to say out loud, even if she doesn't mean it, an AP (Acceptance Prescription) of the intolerable to her various EPs: - "repeat after me even if you don't mean it: even with this part of me that's always afraid..., I now have the right to discover my own life, to exist..." or "even with this part of me that once did its best and kept this problem, now I have the right to change". A very useful phrase to get the patient to utter: "I love and accept myself fully with this fear, with this guilt, with this shame, etc., with this part of me that did its best but doesn't know that now I've grown up...". In the middle and at the end of the session, Emma feels a sense of relief and calm.

By the 3rd and 4th appointments, the patient had regained almost 10 kg. She says: "I don't think about anything anymore, I don't think about scheduling food and always thinking... and yet I haven't become obese! She also testifies to the changed way boys look at her and her desire to find a boyfriend. She only weighs herself once a week. The last two sessions will be devoted to her "little fear that it won't last and that fear will take over again."

At the 5th appointment, the patient has gained back a further 10 kg; she now weighs 45 kg for 1m64 and reports feeling very well. Work continued until the 6th appointment on her fear of returning to her previous state and on her "always too busy mind". At the 7th appointment, Emma is now 55.1 kg and our work comes to an end. Several months later, Emma gives us news: our integrative work has filled her with confidence, she has not relapsed or become bulimic, and she has new emotional and social relationships.

Emma's restrictive eating behavior was a response to the high activation she underwent at the age of 15 (rape): it's how her nervous system responded at the time to help her cope with the unbearable. This could have taken another form, such as compulsive eating with or without obesity (with or without vomiting). During the Limbic Psychotherapy® treatment, with its psycho-educational component, this reaction was described as positive by the practitioner for the dissociated EPs: it's a dialogue in syntony with the EPs, in this therapeutic EP/ANP dyad, and this, during all the sessions. In this way, Emma's eating behavior enabled her to regulate herself in the face of what she had undergone and which, during the sessions, would never be discussed because it was implicit: the rape event was therefore dealt with indirectly, without verbalization. This approach enabled her to stay within her window of tolerance, while at the same time remaining on the borderline, a positive but maladaptive behavior several years after the assault.

From this point of view, it could be said that Emma created for herself (independently of her will) a window of artificial food tolerance that helped her to function. The therapeutic work of Limbic Psychotherapy® therefore directly regulated the underlying traumas, both conscious and unconscious, without the need for verbal therapy. It's worth pointing out (even if this isn't Emma's case) that very often cases of addiction (food, games, shopping, sexual, etc.) also present developmental attachment disorders (ambivalent attachment, disorganized and insecure attachment).

Conclusion

Functional Dissociation® shares a set of cognitive, emotional and behavioral symptoms with structural dissociation. It is this multiplicity of symptoms that requires treatments to be multidimensional. Purely verbal therapies rely on patients' testimony, which they cannot always provide because, as we have seen, many patients are unaware of the root cause of their disorders and come to treatment for other reasons. This is why, in the case of acute or chronic trauma or persistent attachment disorders, non- verbal approaches such as Limbic Psychotherapy® are best suited, especially as no suggestions - even metaphorical ones - will be induced by the practitioner.

Among semi-verbal or non-verbal approaches, integrative therapies focusing on the deeper neurobiology of the disorder are certainly those with the greatest potential. At the frontier between mind and body, these "bottum-up" approaches have the particularity of mobilizing patients' neurophysiological resources, while avoiding any risk of suggestion on the part of the therapist. This was already the hallmark of Integrative Mind-Body Therapy (TICE®), which I have been developing since the 1990s, and it is the essence of Limbic Psychotherapy®, an approach that capitalizes on decades of clinical experience with patients. From this point of view, the therapeutic alliance associated with the Mindfulness approach enables treatment to be carried out in a way that fully preserves the patient's freedom and initiative: it is the patient, not the therapist, who guides the treatment towards the path that authentically corresponds to him or her.

The integration of the personality thus takes place without constraint or distortion, without will or control: there is no suggestion from the practitioner in this non-verbal context. From this point of view, the therapist is merely a guide: he accompanies the patient on the path he himself traces, without being subject to any potentially harmful external influence. This integrative approach enables the therapist to avoid (re)playing the role of aggressor for the patient, a major pitfall of many other approaches. As a result, Limbic Psychotherapy® is both a psychotherapy and a neurotherapy, entirely at the patient's service.

References

- Saillot I, Van der Hart O. Pierre Janet: French Psychiatrist, Psychologist and Philosopher in Pathfinders in International Psychology Charlotte NC: Information Age. 2015;

- Janet P. 1889 Psychological Automatism. Routledge.

- Saillot I. Petit historique de la dissociation (Chap 1, p In M, Kedia J Vanderlinden, G Lopez, et al. Dissociation et mémoire traumatique. Paris: Dunod 2é édition.

- Janet P. 1909 Les névroses. Paris: ré-édition

- Spiegel H. The dissociation-association continuum. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1963; 136:

- Hilgard ER. Divided consciousness multiple controls in human thought and action. BPS. 1979; 70:

- Van der Hart O, Nijenhuis ERS, Steele K. The haunted self: Structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. WW Norton & Co.

- Dell P, O'Neil J. Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders DSM-V and Beyond. Routledge.

- Lanius U, Paulsen S, Corrigan F. Neurobiology and Treatment of Traumatic Dissociation: Towards an Embodied Self. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015; 2:

- Barlow R, Chu J. Measuring fragmentation in dissociative identity disorder the integration measure and relationship to switching and time in therapy. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;

- 11. Martinez-Taboas A, Dorahy M, Sar V, et al. Growing not dwindling: International research on the worldwide phenomena of dissociative disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013; 201:

- Mayer B. La psychothérapie non verbale des traumas. Un autre chemin pour guérir du psychotraumatisme. Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Bateson G, Jackson DD, Haley J, et al. Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science. 1956; 1:

- Mayer B. Functional Dissociation A Clinical Synthesis of DID and Pierre Janetés Psychastenia. Asean Journal of 2022b; 23:

- Mayer B. La dissociation fonctionnelle un concept opératoire entre TDI et psychasthénie. Annales 2022a; 180:

- Van der Hart O, Brown P, Van der Kolk B. Le traitement psychologique du stress post-traumatique de Pierre Annales Médico-Psychologiques. 1989; 9:

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162:

- Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, et al. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala ventral striatum and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002; 26:

- Mayer B. Limbic Psychotherapyé: A Novel Approach to Treat Dissociative States Traumas Attachment Disorders and Their Somatic Dimensions. Int J Psychiatr Res. 2023c; 6:

- Saillot I. The city buried beneath ashes: Pierre Janet La cité enfouie sous les cendres: Pierre Janet enfin ramené é la lumiére. éditorial. European Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. 2018; 2:

- Sabioni P, Le Foll B. Psychosocial and Pharmacological Interventions for the Treatment of Cannabis Use Focus. 2019; 17:

- Kheirabadi GR, Ghavami M, Maracy MR, et al. Effect of addon valproate on craving in methamphetamine depended patients A randomized trial. Adv Biomed Res. 2016; 5:

- Koob GF, Ahmed SH, Boutrel B, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms in the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004; 27:

- Rose ME, Grant JE. Pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine dependence: A review of the pathophysiology of methamphetamine addiction and the theoretical basis and efficacy of pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 20:

- Koob GF, Powell P, White A. Addiction as a Coping Response: Hyperkatifeia Deaths of Despair and Am J Psychiatry. 2020; 177:

- McCaul ME, Hutton HE, Stephens MA, et al. Anxiety anxiety sensitivity and perceived stress as predictors of recent drinking alcohol craving and social stress response in heavy Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017; 41:

- 27. Kwako LE, Schwandt ML, Ramchandani VA, et Neurofunctional domains derived from deep behavioral phenotyping in alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2019; 176:

- Bowlby J. (1999) [1969]. Attachment. Attachment and 2nd ed.

- The World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory data repository: Resources for Substance Use DisordersYouth Treatment programmes for children and adolescents with alcohol use disorders. Data by country.

- Skylstad V, Babirye JN, Kiguli J, et al. Are we overlooking alcohol use by younger children. BMJ Paediatrics 2022; 6:

- Votaw VR, Pearson MR, Stein E, et al. The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment negative emotionality domain among treatment-seekers with alcohol use disorder: construct validity and measurement invariance. Alcohol Clin Exp 2020; 44:

- Porges SW. The Polyvagal Theory: Phylogenetic contributions to social behavior. Physiol Behav. 2003; 79:

- Mayer B. Limbic Psychotherapy®: An Innovative Model for Treating Simple and Complex Somatoform Dissociative States. Am J Appl Psychol. 2023a; 12:

- Mayer B. Limbic Psychotherapy® and the frame of Functional dissociation: quickly healing from dissociative states and chronic trauma. Acta Neurophysiol. 2023b; 4:

- Van der Hart O, Friedman B. A Reader's Guide To Pierre Janet A Neglected Intellectual Heritage. Dissociation. 1989; 2: 3-16.