Alcohol Consumption Patterns among Students at Southern California Universities - A Pilot Study

Author'(s):Riley M. Brown1, James Russell Pike2, Archana More-Sharma3 and Christopher Cappelli1*

1Department of Health and Human Sciences, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, California.

2Grossman School of Medicine, New York University, New York,New York.

3Department of Health Science, California State University,Dominguez Hills, Carson, California.

*Correspondence:

Christopher Cappelli, PhD, MPH, Loyola Marymount University,1 LMU Drive, MS 8888, Los Angeles, California.

Received: 15 Mar 2024; Accepted: 22 Apr 2024; Published: 30 Apr 2024

Citation: Riley M. Brown, James Russell Pike, Archana More-Sharma, et al. Alcohol Consumption Patterns among Students at Southern California Universities - A Pilot Study. Addict Res. 2024; 8(1): 1-4.

Abstract

Introduction: University attendance is a known risk factor for alcohol use and misuse. While past research has shown the severity of this risk depends on several interrelated factors, including peer and family perceptions/ acceptance of alcohol, little research has been conducted into the role individual university culture plays in the initiation and continued use of alcohol.

Methods: Patterns of past 30-day alcohol consumption among students (N=303) attending two Southern California universities, Loyola Marymount University (LMU) and California State University Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), was measured via a cross sectional survey. An analysis was conducted to determine if a student’s perception of overall university alcohol use/acceptance mediated the relationship between peer perception/acceptance of alcohol use and a student’s overall alcohol consumption.

Results: Students attending a non- commuter, majority non-Hispanic white university, consumed significantly more alcohol than their peers attending a commuter, majority Hispanic university (past 30-day use: 70.2% vs. 46.8%; p<.001). The primary mediation model indicated university perception/acceptance was a significant mediator of the relationship between peer use perceptions and past 30-day alcohol use [OR: 2.02 (CI: 1.39, 3.22)].

Conclusion: This study provides evidence that overall university culture may influence and alter alcohol consumption patterns among students. A heightened awareness of peer and university perception of alcohol use may provide potential for universities to develop tactics that reduce alcohol consumption among their student populations.

Keywords

Introduction

Rates of alcohol use and binge drinking among college aged adults remains a major area of public health concern. A number of issues have been known to occur due to over consumption of alcohol, including increased instances of assault, academic shortcomings, sexual assault, alcohol use disorders, and even death [1]. Recent, large-scale national investigations have found over 60% of college- aged adults (18-22) have reported consuming at least one alcoholic drink in the past month, and 27% reported binge drinking at least once in the past two weeks [2]. Further, while rates of male binge drinking have been declining steadily, women’s rates of binge drinking have increased to reach parity with men for the first time [2]. While past investigations have attempted to decern risk and protective factors related to young adult alcohol use, research tends to focus on differences between college students and noncollege youth. However as recent trends indicate a parity in drinking rates among these two groups [2], a more nuanced investigation within the college population may be warranted in an effort to decern predictors and risk factors associated with consumption or over-consumption. One explanation may lie in differences in overall campus culture. In other words, a the population of a specific campus may bring cultural practices with them, and ultimately have direct influence over the choice of the college population to engage or not engage with alcohol.

Past research conducted among college populations has found that an individual’s perception of alcohol use (e.g., fun, necessary for social interaction, everyone drinks, etc.) functions as a risk factor for future alcohol consumption [3]. Findings from a study conducted by Neighbors and colleagues support the relationship between perceived norms of alcohol use amongst one’s peers and alcohol consumption frequency. Specifically, they found that consistent overestimations exist among university students regarding the amount of alcohol that their peers are consuming [4]. Peer influence over an individual’s decision to consume alcohol is largely dependent on peer ties and peer density - two factors that measure one’s interconnectedness within a social networks [5]. However, while studies such as that done by Bravo and colleagues provide valuable information about individual and perceptions of alcohol use among social networks, few studies have investigated the large social environment, the role it has in the formation of use perceptions, as well as the initiation and continuation of alcohol use and binge drinking.

Indeed, cultural approval or disapproval of alcohol consumption heavily influences one’s likelihood to consume alcohol or engage in binging behavior [6]. It is possible that an individual’s cultural background will carry over to exert an influence over the larger, social environment. For example, among different racial and ethnic groups in the US, Caucasian populations tend to demonstrate the highest alcohol consumption rates as well as the second highest level of binging behavior, and Hispanic populations reported slightly lower levels of binge drinking behavior [5]. This disparity in alcohol consumption amongst different racial and ethnic groups may help explain, in part, why alcohol use patterns may vary at universities with differing demographic composition. It is possible that individual cultural practices will be transferred to generate an overall university culture or ‘norm’ regarding acceptance or disapproval of alcohol use. Taken together, it is possible that a university, based on population characteristics, has its own alcohol use culture, which ultimately influences the perception of use, approval of use, and the initiation and continued use of alcohol among college populations. The current study conducted a pilot exploratory study between two Southern California universities to determine what, if any, effect the university attended played in alcohol consumption patterns among a sample of college- aged adults. Specifically, analysis examined the mediation effect university had between peer perception of use and future prediction of alcohol use and binge drinking.

Methods

Students from two universities located in Southern California were selected to participate in this study. Loyola Marymount University (LMU) and California State University Dominguez Hills (CSUDH) are both located in southern California; however, several factors serve to differentiate the student populations at each of these universities. Written consent was obtained from participants in accordance with procedures approved by the LMU and CSUDH Institutional Review Boards. A total of 303 individuals across both universities completed the survey. LMU students who completed the survey averaged 19.8 (±1.1) years old while CSUDH students who completed the survey averaged 22.6 (± 4.7) years of age. At CSUDH, 85.6% of students surveyed were female while at LMU 76.4% of students surveyed were female. Those surveyed at LMU were composed of 25% Asian, 7.3% Black, 19.4% Hispanic, 59.7% Caucasian and 13.7% “other” students. Those surveyed at CSUDH were composed of 10.1% Asian, 6.5% Black, 76.9% Hispanic,11.8% Caucasian and 7.7% “other” students (See Table 1).

Measures

Demographics: This measure asked questions regarding on campus engagement (e.g., Greek life, sports, etc.), marital status, gender, race/ethnicity, age, and current living situation of the student.

Past 30-day use: This measure asked students questions regarding frequency of alcohol consumption during the past 30 days. Response options included “0 occasions,” “1-2 occasions,” “3-5 occasions,” “6-9 occasions,” “10-19 occasions,” “20-39 occasions,” and “40 or more.”

Past 30-day drinking behavior: This measure asked students questions regarding quantity or amount of alcohol consumed during the past 30 days. More specifically, how often the student drank enough to feel pretty drunk or buzzed/tipsy on the occasions during which they did consume alcohol. Response options included “on none of the occasions,” “on few of the occasions,” “on about half of the occasions,” “on most of the occasions,” and “on nearly all of the occasions.”

Peer perception: This measure aimed to establish one’s closest friends’ approval regarding drinking daily, drinking and driving, drinking every weekend and passing out from drinking. Response measured included “strongly disapprove,” “disapprove,” “somewhat disapprove,” “neutral,” “somewhat approve,” “approve,” or “strongly approve.” This measure also aimed to establish on what occasions drinking was considered acceptable (e.g., to have fun, to meet people, on your birthday, after final exams, on holidays, etc.).

University perception: This measure aimed to establish injunctive norms at the university attended by the student. These measures asked the student to consider the opinion of a typical student at their specific university regarding drinking daily, drinking and driving, drinking every weekend and passing out from drinking. Response measured included “strongly disapprove,” “disapprove,” “somewhat disapprove,” “neutral,” “somewhat approve,” “approve,” or “strongly approve.”

Procedure

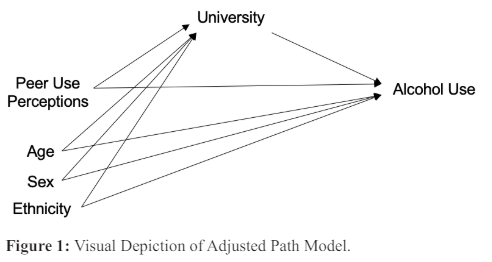

This study utilized a cross-sectional survey administered virtually throughout the fall 2020 semester. A mediation model was used to develop odds ratios and other statistical representations of the data to allow for conclusions. University attended functioned as the mediator with the predictors, or independent variables, being peer use perception. Alcohol consumption functioned as the outcome as well as the dependent variable. Covariates included age, sex, and ethnicity. All statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SAS v9.4. Statistical analysis included percentages, odds ratios, and parameter estimates within a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

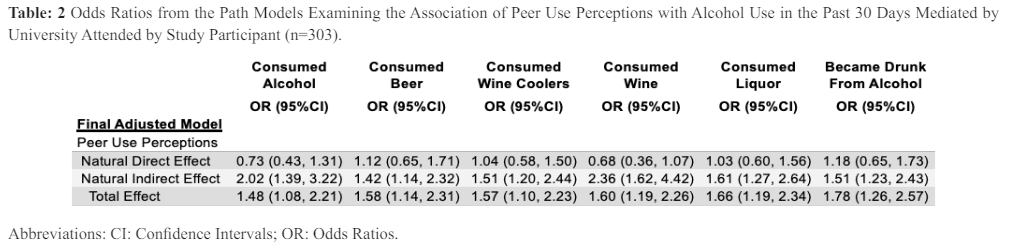

The primary mediation model (Figure 1) indicated university perception or acceptance (i.e., norms) of alcohol use was a significant mediator of the relationship between peer use perceptions and past 30-day alcohol use [OR: 2.02 (CI: 1.39, 3.22)]. Results also indicated that students attending Loyola Marymount University consumed a statistically significantly greater amount of alcohol during the past 30 days than those attending California State University Dominguez Hills (past 30-day use: 70.2% vs. 46.8%; p<.001). Further, students attending LMU also reported a greater number of occasions drunk (past 30-day use: 49.2% vs. 19.2%; p<.001). When demographics were controlled for and data was mediated by university attended by the study participant, peer use perceptions had significant impacts on alcohol consumption within the past 30 days [peer use perceptions: OR: 1.48 (CI: 1.08, 2.21)] (See Table 2).

Note: Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated from a probit regression (Gaynor, Schwartz, & Lin, 2019) with a theta parameterization that employed the weighted least squares method. Indirect effects calculated using 10,000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples. The structural path model included family and peer use perceptions as latent variables derived from categorical confirmatory factor analysis measurement models. Full-information maximum likelihood was utilized to address missing values. Model 1 depicts the unadjusted, crude estimate. Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity.

Discussion

Results indicated that students attending a primarily younger (average age: 20), white non-Hispanic, non-commuter university consumed greater amounts of alcohol than those attending a primarily older (average age: 25), Hispanic, commuter university. The results of this study are consistent with previously reported alcohol consumption tendencies among different ethnic groups [5]. As was observed in this study, greater ethnic diversity (e.g. as seen at CSUDH), has been correlated with decreased alcohol binging behaviors among students [7]. Not only did students attending a younger, more white, and less commuter university consume more alcohol overall, but also demonstrated higher levels of binging behavior when compared to individuals attending a non- traditional, older, commuter university. Overall university culture has not been investigated as a mediator of alcohol use in previous studies. While not directly measuring culture this study attempted to quantify this variable by focusing on related factors, such as student body composition (e.g., age, ethnicity), and injunctive norms (e.g., peer, parental). It is important to juxtapose this data with the varying cultures at these two different universities - this includes analyzing both peer perceptions of alcohol consumption as well as university perceptions. In doing so, this study was able to determine that overall university culture may in fact influence and alter alcohol consumption patterns among students. Indeed, past research has shown attending a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI), serves as a protective factor against alcohol use [8].

One potential explanation for this difference in university culture may be due to the number of students living on campus. Specifically, over 50% of LMU’s student body resides on campus while only 1% of CSUDH’s student body resides on campus. A significantly denser concentration of students living away from home may lead to higher levels of alcohol consumption [9]. Research conducted by Lorant and colleagues supports the idea that students living on campus and in dormitories with a higher number of roommates increases alcohol consumption [10]. The influence of peer perceptions of alcohol consumption was further studied by Maddock and Glanz who found that normative beliefs act as a significant mediator in the relationship between alcohol use and social standards [11].

A second explanation for this difference in consumption patterns may be due to ethnic differences among the population, which in turn influences the perception of alcohol norms at the university level. For example, typically Hispanic individuals report reduced consumption compared to their non-Hispanic counterparts. While speculative, it is possible that these university level norms of alcohol use are ultimately created through a merging of beliefs from the student population, and individuals will shift their beliefs to more align with the predominant belief on that campus [12]. In other words, a student of any gender or ethnicity attending an institution primarily represented by individuals from ethnic/ cultural backgrounds that do not consume high levels of alcohol, may alter their beliefs regarding alcohol use to align with the majority norm of lower levels of drinking more closely.

These results may be utilized by universities to aid in the development of prevention programming aimed at reducing alcohol consumption among their student population based directly on the beliefs of their student body. Further studies on this subject may benefit from analyzing student behavior when under the influence of alcohol. This information would provide a basis by which to advance awareness of the effects of varying student alcohol consumption patterns on things such as tendency towards violence, inappropriate behavior, and/or deficiency in schooling.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study that merit discussion. First, this study was cross sectional, so determining causality will be limited. However, based on known drinking rates among the general population, this data provides evidence that overall culture of a university may influence drinking rates. Second, the measure of culture in this work is of limited utility, as it was measured indirectly through various demographic variables, such as ethnicity, age, and percent of students living on campus. However, previous investigations have shown ethnic group membership to be a significant predictor of various health behaviors, including alcohol use and binge drinking [5].

References

1. Hingson RW, Zha W, White AM. Drinking Beyond the Binge Threshold: Predictors Consequences and Changes in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2017; 52: 717-727.

2. Patrick M, Schulenberg J, Miech R, et al. Monitoring the Future Panel Study annual report National data on substance use among adults ages 19 to 60, 1976-2021. University of Michigan Institute for Social Research: Ann Arbor. 2022.

3. Bravo AJ, Prince MA, Pearson MR. College-Related Alcohol Beliefs and Problematic Alcohol Consumption Alcohol Protective Behavioral Strategies as a Mediator. Subst Use Misuse. 2017; 52: 1059-1068.

4. Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, et al. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2006; 67: 290-299.

5. Sudhinaraset M, Wigglesworth C, Takeuchi DT. Social and Cultural Contexts of Alcohol Use Influences in a Social- Ecological Framework. Alcohol Res. 2016; 38: 35-45.

6. Wells GM. The effect of religiosity and campus alcohol culture on collegiate alcohol consumption. J Am Coll Health. 2010; 58: 295-304.

7. Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School Of Public Health College Alcohol Study focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008; 69: 481-490.

8. Vaughan EL, Chang TK, Escobar OS, et al. Enrollment in Hispanic Serving Institutions as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Drinking Norms and Quantity of Alcohol Use Among Hispanic College Students. Subst Abus. 2015; 36: 314-317.

9. Carter AC, Brandon KO, Goldman MS. The college and noncollege experience: a review of the factors that influence drinking behavior in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010; 71: 742-750.

10. Lorant V, Nicaise P, Soto VE, et al. Alcohol drinking among college students: college responsibility for personal troubles. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: 615.

11. Maddock J, Glanz K. The relationship of proximal normative beliefs and global subjective norms to college students alcohol consumption. Addict Behav. 2005; 30: 315-323.

12. Cappelli C, Ames SL, Xie B, et al. Acceptance of drug use mediates future hard drug use among at-risk adolescent marijuana tobacco and alcohol users. Prevention Science. 2021; 22: 545-554.