Experience of, and Perceptions on, Disrespectful Treatment from Health Workers, by Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in Southeastern Nigeria

Author'(s): Adinma JIB1*, Oguaka VN1, Ugboaja JO1, Umeononihu OS1, Adinma Obiajulu-ND1, Okeke OL2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University and Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria.

2Department of Nursing sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka.

*Correspondence:

Prof J.I.B Adinma, Department of OBS/GYN, Nnamdi Azikiwe University and Teaching Hospital, PMB: 5025 Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria, Tel: +2348037080814.

Received: 30 October 2019 Accepted: 18 November 2019

Citation: Adinma J.I.B, Oguaka VN, Ugboaja JO, et al. Experience of, and Perceptions on, Disrespectful Treatment from Health Workers, by Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in Southeastern Nigeria. Gynecol Reprod Health. 2019; 3(6): 1-6.

Abstract

Background: Disrespectful maternity care is a sexual and reproductive right abuse that can discourage women from seeking maternal care in formal healthcare facilities.

Objective: To determine the experience of, and perceptions on disrespectful treatment from health workers, by pregnant antenatal clinic attendees in Anambra, Nigeria.

Methodology: Questionnaire-based, cross-sectional study of 250 pregnant women from six health facilities in Anambra, Nigeria. Data analysis performed using SPSS version 22.0. Statistical comparison of variables employed chi-square test, Significant at p-value <0.05 at 95% confidence interval.

Results: Thirty-one participants (12.4%) had experienced disrespect and abuse (D&A), most commonly during labour and delivery 74.2%. Physical Abuse most commonly occurred 13(41.9%). Respondent’s experience of disrespectful care was highest from TBAs (50%) and lowest for Obstetrician (1.8%). Similarly, respondent perceptions on respectful care was best for obstetricians (RCI=0.99), and least for the TBAs (RCI=0.67). Respondents also perceived that promotion of respectful maternity care is best achieved through healthcare provider education, 68 (27.2%) followed by provision of free maternal healthcare, 65 (26.0%).

Conclusion: Inspite of the low level of D&A in this study, no pregnant woman should be subjected to undue mistreatment during maternity care. Improving the quality of training of birth attendants, to incorporate respectful maternity care is necessary, together with ensuring the wide-scale access of pregnant women to skilled obstetricians.

Keywords

Introduction

Every childbearing woman (and her baby) deserves respectful care and protection during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium. Although the concept of Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) had evolved and expanded over the past few decades, no instrument had specifically delineated the role of human rights in childbirth until recently [1]. As birth is being medicalized, there has been growing concerns over “obstetric violence” and advocates have emphasized the need for humanization of birth and woman- centred approach to maternity care. Disrespect and abuse (D&A), a concept closely related to obstetric violence, are global issues and are violations of basic human rights [2]. Women who have experienced or who anticipate mistreatment from health workers in a health facility are less likely to seek antenatal care and delivery in such facility in future. Dignified care is a key factor in ensuring increased facility births by women. Therefore, efforts to increase the use of facility-based maternity care services in low-resource countries are unlikely to achieve desired gains without improving quality of care and focusing on women’s experience of care [3]. Seven categories of D&A have been recognized and include: physical abuse, non-consented clinical care, non-confidential care, non-dignified care, discrimination, abandonment and detention in health facilities [4]. This has been updated by a systematic review to include: physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma and discrimination, failure to meet professional standards of care, poor rapport between women and providers, health system conditions and constraints [5]. Physical abuse can be in the form of restraint, beating, slapping or pinching during labour, giving or suturing episiotomy without anaesthesia. Non-confidential care and violations of privacy can occur inadvertently due to limited physical facility and space especially in low-resource settings. Non-consenting care can be in the form of induction of labour and caesarean sections without the consent of the women, while neglect and abandonment can be due to denial of pain relief during labour. Discrimination arises as a result of HIV status, socio-economic class or ethnicity while detention in health facility is usually as a result of failure to pay hospital bills by the women.

In Nigeria, disrespect, abuse and non-dignifying maternity care experienced by women have been reported in a few studies. For instance, in Enugu, southeast Nigeria, as high as 98.0% of postnatal women reported at least one form of disrespectful and abusive facility-based care during their last childbirth [6]. Of these, 54.5% received non-consented services, 35.7% were physically abused, 29.6% received non-dignified care, 29.1% were abandoned/ neglected, 26.0% had non-confidential care, while 22.0% were detained and 20.0% were discriminated against6. In the same study, 17%, 9%, 7% and 2% respectively admitted to have been restrained, given/had episiotomy repaired without anaesthesia, beaten/slapped/pinched during labour or sexually abused by a health worker [6]. Violations of privacy or confidentiality as documented in Sagamu, South west Nigeria was 16.5% [7], while non-dignifying care varied widely in Nigeria ranging from 11%- 71% [8]. In Zaria Northern Nigeria, it was reported that 12% of parturient women were denied labour companionship [9], while 66% of parturient women in Enugu south east Nigeria were denied request for labour analgesia10and as such they felt neglected and abandoned.

Despite the high prevalence of D&A in Nigeria, only a handful of studies have been done in that respect and even fewer have tried to document the causes and proffer solutions. Some studies have speculated about systemic problems that may perpetuate D&A in Nigeria [8]. Acceptance of D&A as being normal in facility- based childbirth, financial barriers, women’s lack of autonomy and empowerment, poor quality clinical training related to provider- patient interaction, a lack of national laws or policies and health care workers’ demoralization due to weak health systems are cited in most instances [8].

As part of the campaign to minimize D&A in Nigeria, the White Ribbon Alliance (WRA) is the country’s main current campaign organization that is domiciled in Niger state, north central Nigeria. It is a “Citizen-led Accountability for Maternal, New-born and

Child Health (MNCH), with the goal to strengthen engagement platforms between Government and citizens to achieve sustainable improvements in the quality of care for maternal, new-born and child health services. This is achieved by organizing community dialogues and training of citizens about their health rights and the need to hold their leaders accountable [11].Through the national advocacy campaign of WRA Nigeria, Nigeria became the first country to officially establish RMC as a standard of practice in 2013 [11]. Other means of curbing D&A that have been suggested include the involvement of policy-makers, professional associations and community organizations [8]. If these are successfully achieved and implemented, then the women will be sure to receive dignifying quality care and a memorable birthing experience.

This study has been undertaken amongst pregnant antenatal clinic attendees to determine their experience of disrespectful treatment from health workers, and elicit their perceptions on the disposition of the health-workers towards respectful maternity care. The outcome of this study may inform the development of protocols that will optimize the protection of the reproductive rights of the woman receiving care during antenatal, delivery and postpartum period.

Subjects and Methods

Two hundred and fifty pregnant women attending six different health facilities in Anambra state, south east Nigeria were surveyed in this interviewer-administered questionnaire-based, cross-sectional study. These facilities included Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi – ATertiary/referral Hospital; Holy Rosary Specialist Hospital, Water side Onitsha – A secondary voluntary agency (mission) hospital; Chidera Hospital, Nnewi - a Private hospital; Primary Health Centre, Nnobi and a Traditional Birth Attendance (TBA) Centre in Nnewi. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the ethics committee of Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital. While oral permission for the study was obtained from the other health facilities that did not have any standing ethics committee. Only antenatal clinic attendees who had delivered at least one baby and gave their consent were selected by simple random sampling technique and drawn into the study. Nulliparous patients were excluded since they had not had any experience with delivery. Verbal consent was obtained from the participants after due explanation of the objective of the study. The questionnaires were administered by trained interviewers, consisting of clinical, medical and nursing students, under the supervision of a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist. The age, parity, gestational age, experience of disrespect and abuse (D&A) in their last pregnancy as well as category of healthcare provider that managed them were documented. The measures they think could be taken to curtail D&A were also noted. Completed questionnaire were analysed using SPSS Version 22.0, and data displayed in tables and figures. Statistical comparison of data employed chi-square test, with p-value of ≤ 0.05 at 95% confidence interval, considered as significant.

The respondent’s perception of respectful care with respect to the cadre of healthcare provider was computed using respectful care index (RCI), which was determined by the sum of good and fair rating divided by the total number of respondents for each category of healthcare provider (RCI = G+F/n).

Results

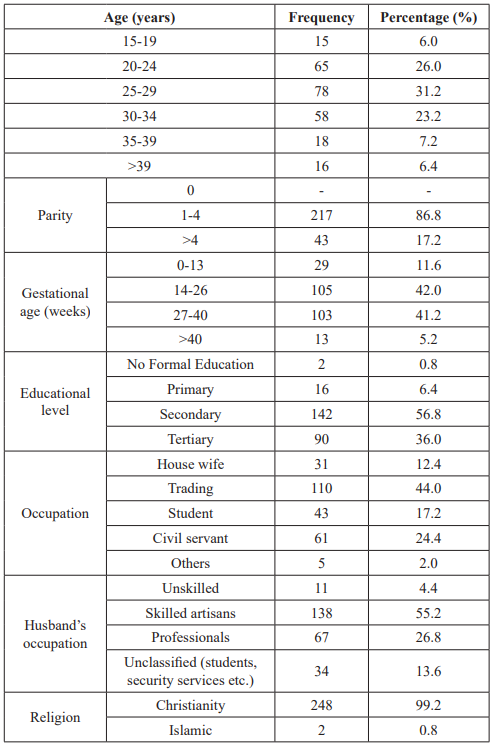

Data on two hundred and fifty antenatal women who were interviewed was obtained and presented below. The bio-social distribution of the participants is presented in table 1. Up to 31.2% of the participants were between the ages of 25 to 29 years while 6.0% were at most 19 years and 6.4% were above 39 years of age. While 17.2% were grand multiparous, 86.8% were primiparous/ multiparous. Those who had tertiary education were up to 36.0%, while 56.8% had secondary education as their highest educational attainment and 0.8% had no formal education. Trading was the predominant occupation among the participants (44.0%), while 12.4% were unemployed housewives and 17.2% were students. Most of the husband of the respondents were skilled artisans (55.2%); while 26.8% were professionals.

Table 1: Bio-social characteristics of the participants.

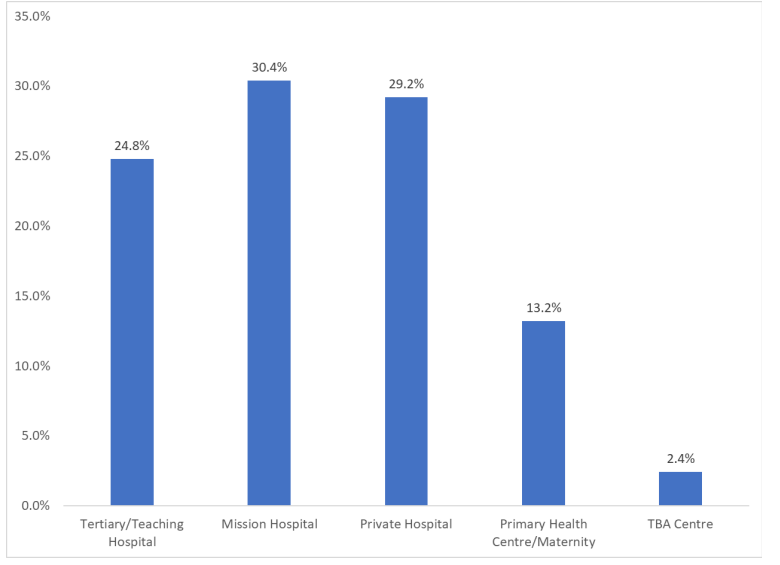

Figure 1 shows the distribution by the categories of health facilities attended by the participants in their last pregnancy. Upto 76 (30.4%) attended mission hospitals; 73 (29.2%) attended private hospitals; and 62 (24.8%) attended a tertiary hospital. Over 13% attended a primary health centre/maternity while 2.4% attended a TBA centre.

Figure 1: Category of health facilities attended by the respondents in their last pregnancy.

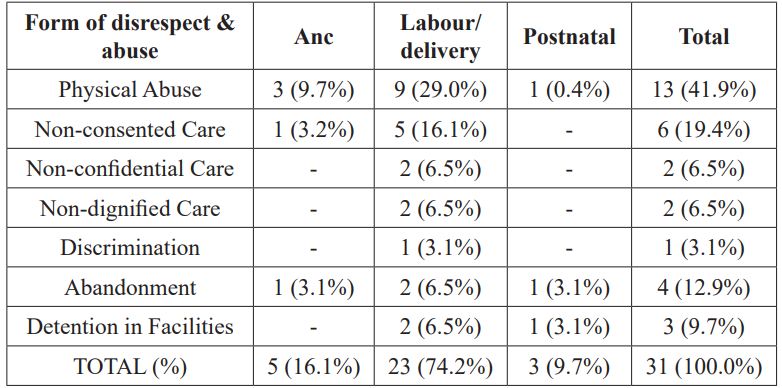

The distribution by forms of disrespectful care/abuse experienced by the respondents for type of maternal healthcare is shown in table 2. A total of 31 (12.4%) of the participants had experienced a form of disrespectful care in the course of their last pregnancy. Disrespectful maternal care most commonly occurred in Labour/ delivery 23 (74.2%), followed by antenatal care 5 (16.1%), and postnatal 3 (9.7%) periods. Physical Abuse was the most common form of disrespectful care experienced by the respondent 13 (41.9%), followed by non-consented care (19.4%), while the least common was discrimination 1 (3.1%). Other forms of D&A experienced by the participants included non-confidential care (6.5%), non-dignified care (6.5%), abandonment (12.9%) and detention in facilities (9.7%).

Table 2: Distribution by forms of disrespectful care/abuse experienced by the respondents for type of maternal healthcare.

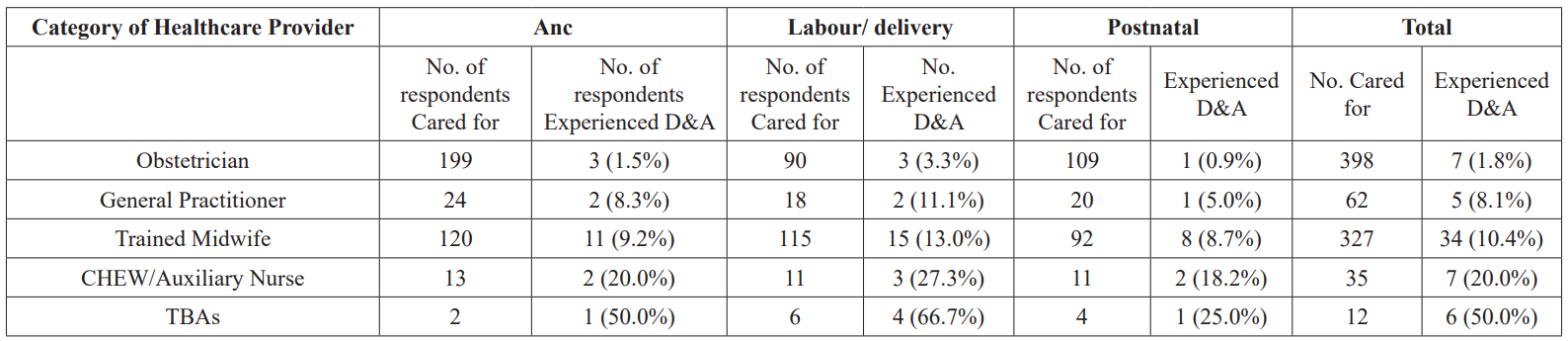

The distribution by cadre of healthcare provider attending to respondent’s last pregnancy for the type of maternal care and D&A experienced is shown in table 3. Participant’s experience of D&A was highest among those attended to by TBAs 6 (50%); followed by CHEW/Auxilliary 7 (20%); trained midwife 34 (10%); general practitioner 5 (8.1%), and the lowest amongst those attended to by the Obstetricians 7 (1.8%). This difference in experience was significant, between the obstetrician and other cadres of health workers (p<0.05).

The intrapartum period constitutes the most vulnerable period for D&A irrespective of the category of healthcare provider concerned, ranging from as low as 3.3% among those managed by the obstetricians to as high as 66.7% among those managed by the TBAs. The least vulnerable period is the postpartum period with the prevalence of 0.9% among those managed by the obstetrician and up to 25.0% among those managed by the TBAs. The vulnerability difference was also significant between the obstetrician and other health providers (p<0.05).

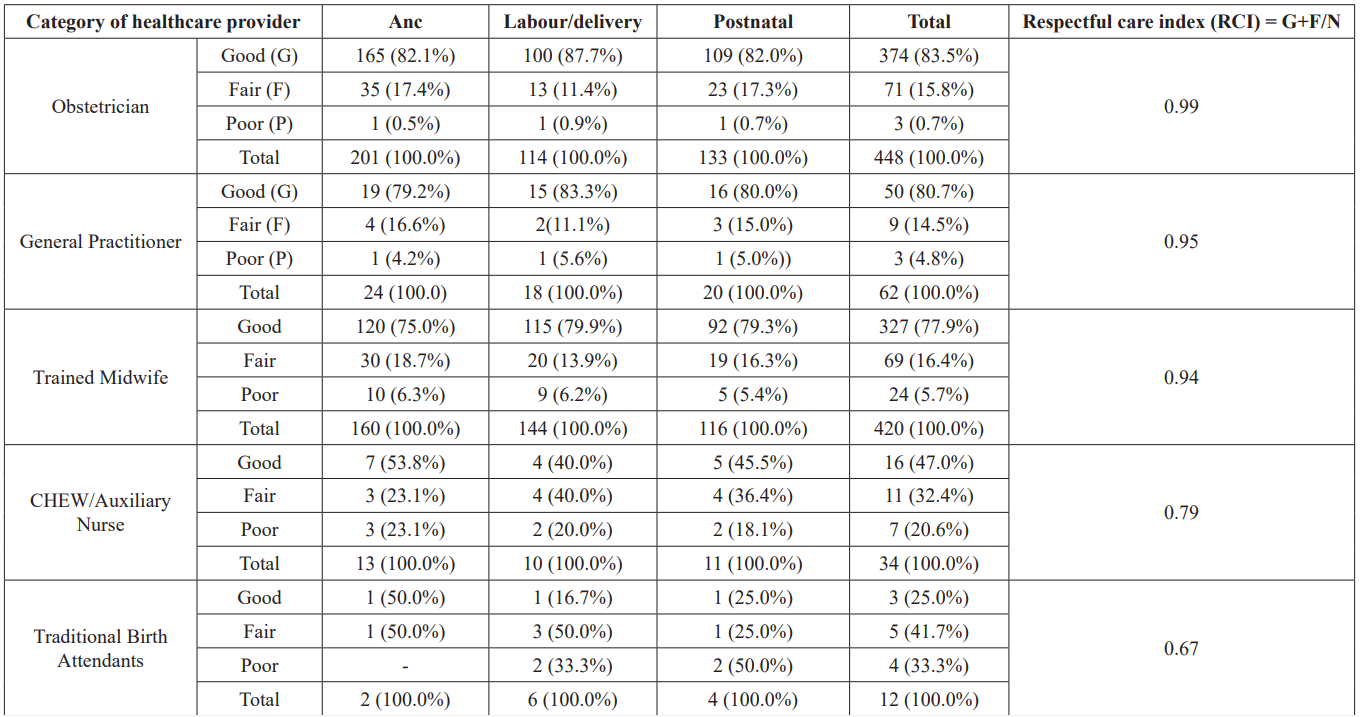

The respondents’ perception of the level of respect accorded them in their last pregnancy is shown in table 4. The participants who were managed by the obstetricians were most satisfied as 83.5% and 15.8% respectively rated their overall experience as either good or fair, while only 0.7% overall rated their experience as poor. Next in terms of satisfaction were those who were managed by the general practitioners, as 80.7% and 14.5% respectively rated their experience as either good or fair, while 4.8% rated it as poor during their last pregnancy. The trained midwives offered good or fair satisfaction rates of 77.9% and 16.4% respectively while 5.7% had poor satisfaction during their last pregnancy. The auxiliary nurses and traditional birth attendants were ranked the least as the participant’s satisfaction with their care in their last pregnancy were lower. The auxiliary nurses were rated to have offered either good or fair care by 47.0% and 33.4% respectively of the participants, while 25.0% and 41.7% respectively judged the services rendered by the TBAs to be either good or fair respectively. Respectful care index (RCI) measures the overall respondent’s perception of respectful care experienced with respect to the category of the healthcare provider. RCI was high for the Obstetrician 0.99, followed by the general practitioner 0.95 and least for traditional birth attendants 0.67.

Table 3: Distribution by cadre of healthcare provider attending to respondent’s last pregnancy for type of maternal care and D&A experienced.

Table 4: Distribution by cadre of healthcare provider for respondent’s perception of respectful care to them.

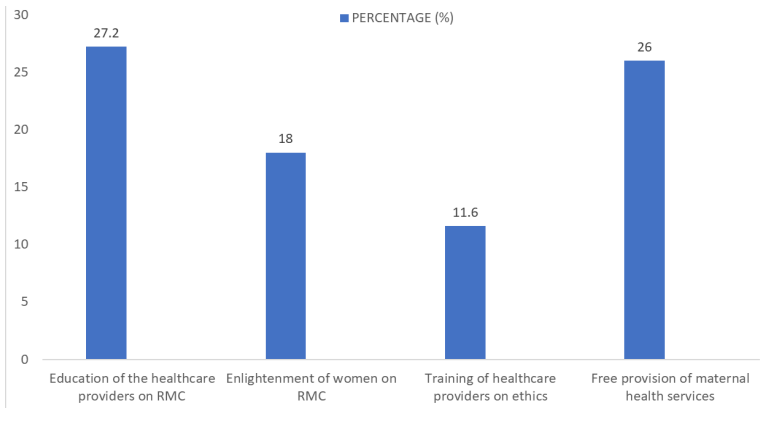

Figure 2 shows the distribution by the recommendations of the respondents on promotion of respectful maternity care. Sixty-eight (27.2%) recommend healthcare provider education on RMC; 45 (18.0%), women enlightenment on RMC; 65(26%), provision of free maternal health services; and 29 (11.6%), training of healthcare providers on ethics. Other recommendation includes punitive measures (8.4%), RMC advocacy to hospital management (7.2%).

Figure 2: Distribution by respondents’ recommendation on the promotion of respectful maternity care.

Discussion

This study shows that 12.4% of the pregnant women interviewed experienced disrespectful care during their last pregnancy, delivery and postpartum period. This prevalence is low when compared to the 98% recorded by Okafor et al. in Enugu Nigeria [6], and 79.1% recorded by Makumi in Kenya [12]. A systematic review on disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria puts the prevalence of D&A at 11% to 71% [13]. The reason for the low prevalence in this study is not clear. It is tempting however to suggest that the low social class to which most of the respondents in this study belong may have informed their misapprehension of what should really constitute disrespectful treatment to them during maternity care. They would therefore have regarded many of the abusive care meted to them as normal. Furthermore, it has been speculated that women who are neither aware of their rights nor been exposed to any other system of care are not sensitive to the D&A and see such as normal pattern of treatment [14].

Disrespect and abuse were experienced mostly during labour/ delivery accounting for 74.2%. Labour and delivery usually constitute the most demanding and stressful period for a pregnant woman and her caregiver alike and this may account for the high rate of disrespect and abuse experienced during the period.

Physical abuse was the most common form of disrespectful treatment experienced by the women in this study occurring in 41.9% of cases. A previous report by Okafor et al. had recorded an overall prevalence of 36.0% for physical abuse among parturients [6]. Non-consented care was recorded in 19.4% of the cases. This was in the form of the use of episiotomies, induction or augmentation of labour etc. A prevalence rate of 54.5% was recorded by Okafor and co-workers6. Detention in health facilities was noted in 3 participants (9.7%), mainly due to non-settlement of hospital bills. Okafor et al. recorded a 22.0% prevalence of detention in health facilities for similar reasons [6].

Other forms of D&A noted in this study such as abandonment (12.9%), non-confidential care (6.5%), non-dignified care (6.5%), discrimination (3.1%) were also lower than those recorded elsewhere6,7. The major reason for non-confidential care was lack of space and facilities.

Overall, less than 2% of the participants managed by the obstetrician reported D&A while up to 50.0%, the highest recorded in this study were reported by those managed by the TBAs. Those managed by the other healthcare providers such as the general practitioners, trained midwives, CHEWs/auxiliary nurses reported increasing prevalence of D&A in that order (Table 3). This order increasingly correspond to the extent of obstetrics training attributable to the various professional cadres. Therefore, occurrence of D&A is noted to be inversely proportional to the training and professionalism of the healthcare provider, being lowest among those cared for by the Obstetrician, the highest cadre of professionals, and highest among those cared for by the TBAs, the least cadre of birth attendants.

The participants’ perception on RMC was highest for the Obstetrician (RCI = 0.99) and lowest for the TBAs (RCI=0.67). Similarly, the level of dissatisfaction on RMC was highest for TBAs (33.3%) and lowest for the obstetrician (0.7%). Interestingly, client satisfaction of maternal services received by a similar population in primary health centres in the same region of the state where this study was carried out was over 90% and a dissatisfaction level of 6.8% [15].

The participants’ recommendation on the promotion of RMC, was high for the education of healthcare providers (27.2%). This is necessary because if the healthcare providers realise how much they hurt the self-esteem of the women under their care, it may help them modify their approach to the delivery of maternal services. The provision of free maternal services will also help reduce the possibility of detention in health facilities for inability to settle accrued hospital bills. It may also reduce discrimination as a result of social status since the financial capability of patients will no longer determine the level of maternal services the women can have access to. Almost a fifth of the participants (18.0%) recommended that enlightenment of the women seeking or who may seek maternal services on RMC is important in promoting RMC. This is important because if the women are sensitised and they realise their rights are been infringed upon, they will not normalise disrespect and abuse. That way, they will be able to speak out and the providers will be made to face the consequences of mistreatment during maternal care. Less than 10% of the women believed in the use of punitive measures against the healthcare providers. These punitive measures could be in form of loss of licence to operate or boycott by the clients themselves. Most of the systemic issues to which disrespect and abuse in maternity care has been attributed are demonstrable in this study- including the acceptance of D&A as being normal in facility-based childbirth; financial barriers; women’s lack of autonomy and empowerment; poor quality clinical training related to provider-patient interaction, a lack of national laws or policies and health care workers’ demoralization due to weak health systems [8].

Women’s satisfaction and good experience with maternity care are key factors that have been identified as the stimuli to encourage women (especially in the developing countries) to opt for facility- base care and delivery. This study has shown that the likelihood of this satisfaction is higher with the higher cadre of healthcare provider. Therefore, efforts should be geared towards improving the access of the pregnant women to the services of the higher cadre professionals. This can be achieved through policies that will encourage the training, specialization and re-training of healthcare professionals. Creation of job and enabling environment will go a long way to minimizing brain drain and quest for the golden fleece elsewhere.

In terms of promoting RMC and minimizing D&A, there should be strong will on the part of stake-holders to educate the healthcare providers and to sensitize the management of maternal health facilities to put in measures to curb the menace. Public enlightenment is also vital because if the women are sensitized, they will understand that RMC is their right and as such will be able to recognize and report cases of D&A.

The use of punitive measures against persons or facilities that condone persons who perpetrate D&A may also be necessary under certain circumstances if enabling laws are enacted.

Finally, the policy-makers should work towards provision of free and accessible maternal health services to the generality of the populace devoid of out-of-the-pocket payment for services.

References

- https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/index.cfm?-ID=publications&get=pubID&pubID=189

- https://www.mhtf.org/2017/04/11/respectful-maternity-care-a-basic-human-right/

- Tunçalp Ö, Were WM, MacLennan C, et Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns - the WHO vision. BJOG.2015; 122: 1045-1049.

- Bowser D, Hill Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth: report of a landscape analysis. Washington DC: USAID. 2010.

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS medicine. 2015; 12: e1001847.

- Okafor II, UgwuEO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2015; 128: 110-113.

- Lamina M, Sule-Odu AO, Jagun OE. Factors militating against delivery among patients booked in Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu. Nigerian journal of medicine. 2004; 13: 52-55.

- https://www.mhtf.org/2017/05/12/disrespect-and-abuse-during-childbirth-in-nigeria/

- Sule ST, Baba SL. Utilisation of delivery services in Zaria, Northern Nigeria: Factors affecting choice of place of East Afr J Public Health. 2012; 9: 80-84.

- Chigbu CO, Onyeka Denial of pain relief during labor to parturients in southeast Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011; 114: 226-228.

- https://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/nigeria/

- http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/93224/Makumi%2C%20Ishmael%20W_abuse%20of%20women%20during%20facility%20based%20deliveries.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

- Ishola F, Owolabi O, Filippi Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria: A systematic review. PLOS One. 2017; 12: e0174084.

- Moronkola OA, Omonu JB, Iyayi DA, et al. Perceived determinants of the utilization of maternal health-care services by rural women in Kogi State, Tropical Doctor. 2007; 37: 94-96.

- Nnebue CC, Ebenebe UE, Adinma ED, et al. Clients' knowledge, perception and satisfaction with quality of maternal health care services at the primary health care level in Nnewi, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2014; 17: 594-601.